Translate Page

How a Broadway birthday tradition shaped my life

---

They say a mother always knows.

Even before a boy comes to realize he is "that way," it will be evident to his mother that he is destined to live his life as part of that special class of humanity: A lover of musical theatre.

My own mother sensed this future for me and, thanks to the theatre gods, did not have to look long for the vehicle to introduce me to the art form. A musical about a boy roughly my age was running on Broadway: the original production of Lionel Bart's Oliver! I had no idea what was in store for me on my 10th birthday. From our perch in the upper balcony, I beheld a panoply of characters, singing and dancing to one of theatre's most tuneful scores, on a wondrous set that was always in motion. I had only a vague sense of the story, but the sounds of laughter and applause were electrifying—I wanted them for myself. After our outing, my parents bought me the original cast album, which I played repeatedly.

The year between birthdays became a bit more bearable knowing I'd be seeing another musical at the end of it. The really popular shows, like Fiddler on the Roof, Funny Girl and Hello, Dolly!, sold out months in advance, and my mother may have thought I wasn't yet mature enough for "adult" material. But Baker Street was based on the Sherlock Holmes stories and, like Oliver!, had a chorus of ragamuffins: the Baker Street Irregulars. Fritz Weaver as Holmes, Inga Swenson as Irene Adler and Martin Gabel as Professor Moriarty are actors I appreciate now but who were unfamiliar to the 11-year-old me. The score wasn't memorable, nor did the visuals make much of an impression. But my strongest memory of Baker Street is of wanting to go back into the theatre to see it again.

With advance planning, my mother was able to secure tickets to Fiddler for my 12th birthday. She prepared me for the serious aspects of the show, believing I was ready for more advanced themes. But something important had happened the summer before—I had been in a show myself. Initially, I was cast just as one of the ballplayers in my summer camp's production of Damn Yankees, but 10 days before the premiere at parents' weekend, our Mr. Applegate got sick and had to go home. I was promoted from the ranks and delivered the goods, including a showstopping rendition of "Those Were the Good Old Days." Soon I started drama lessons and, as I sat in the audience at Fiddler, I experienced the dual perspective of spectator and player. Not knowing who Herschel Bernardi was, I felt no disappointment when his understudy, Harry Goz, played Tevye for our performance. Since that day, I have tempered my disappointment at not seeing a scheduled performer with the anticipation of seeing someone seize an opportunity, just as I had at summer camp. (I also demanded a crash course in bar mitzvah training, something my agnostic mother hadn't bargained on. My haftorah recitation was another showstopper.)

Man of La Mancha was next. However, my birthday was in October and tickets were not available until February. So began a new tradition: celebrating the milestone on a day other than my actual birth date. My mother could get only one ticket, so I saw the show by myself and discussed it with her afterward. The original Cervantes/Don Quixote, Richard Kiley, had been replaced by such notables as José Ferrer and John Cullum, but by the time I saw the show, David Atkinson was my Knight of the Woeful Countenance opposite Bernice Massi as Aldonza/Dulcinea. Irving Jacobson, the original Sancho Panza, was still in the cast, as was Robert Rounseville as The Padre. It was my first encounter with a thrust stage, and the drawbridge that was lowered and raised was awe-inspiring. What started four years earlier as a trip to the theatre on my birthday had metamorphosed into a communal cultural experience not necessarily tied to a specific date, or even shared simultaneously.

The late 1960s produced several fine musicals, but fewer per season than before, with more flops littering Shubert Alley, providing poster art for the restaurant Joe Allen, the newly opened Theatre District hangout still going strong today. 1968 was an especially good year for Joe Allen. Few musicals from the previous season survived the Actors' Equity strike and the summer doldrums. One that had, Hair, was deemed inappropriate for someone about to turn 14. The solution: a series of three piano recitals by Beveridge Webster commemorating the 50th anniversary of the death of French composer Claude Debussy, one of my favorites. This introduced me to the concept of subscriptions, which would swallow a considerable portion of my income for many decades.

The challenge of 1969 was finding a show that neither my mother nor I had already seen. The obvious choice would have been 1776, but my mother (on my advice) had already gone, which freed me up to see it on my own. I had already taken in Hello, Dolly! with its all-Black cast (though without Pearl Bailey), as well as Promises, Promises. But an Off-Broadway musical called Promenade had created such a stir among the critics that we decided it was worth a visit. Written by experimental theatre pioneers María Irene Fornés and Al Carmines, it was a kind of theatre new to us both. However, we attended with open minds and were rewarded with a genuinely fun time, albeit without much comprehension.

If nothing else, Promenade paved the way for me to suspend my expectations about linear storytelling, which has served me well not only in theatre but in dance and the visual arts. I was thrilled to encounter Shannon Bolin, familiar from the original cast recording of Damn Yankees, as well as future favorites Alice Playten and George S. Irving. Madeline Kahn had already left the cast and was replaced by understudy Marie Santell. Unbeknownst to us, my father's brother, my Uncle Reuben, was dating Santell at the time. Tagging along to one of her voice lessons, my uncle met her teacher, Laura Thomas, who soon became my aunt.

I had already begun composing music when Company became my birthday show in 1970. I've previously written about my visceral reaction to this seminal work by Stephen Sondheim. Its form—a series of vignettes rather than a traditional story—grew out of its origin as a group of short plays by George Furth; but its confidence in construction and use of music and lyrics echoed the creativity I had seen in Promenade. With Company, I pivoted from wanting to be in musicals to wanting to write them. Soon I was contributing songs to my college musical revues. I even got as far as membership in the prestigious BMI Musical Theatre Workshop under the tutelage of the legendary Lehman Engel. This might well have been my mother's goal all along, though my life ultimately took a different turn.

My next birthday show had to wait until I returned for my first winter break from college. The opportunity to see a musical by Leonard Bernstein was too good to pass up, so a revival of On the Town was an easy choice. A cast particularly strong among the women—Phyllis Newman, Bernadette Peters and Donna McKechnie—along with Ron Husmann, Remak Ramsay and Jess Richards as the visiting sailors, promised a good time. So why was I so disappointed? Everything felt wrong. I had seen few revivals at that point, but enough to sense a distrust in the material among those responsible for this production. Everyone was working too hard, and the effort showed. To be fair, the world was in a different place than when the show premiered in 1944; a very different war colored our lives. And I was in a different place, too, from the vantage point of what I expected from the theatre. Thanks to the one-two punch of Company and Follies, everything I saw was filtered through the aesthetic of Stephen Sondheim—unfair, albeit understandable for a 17-year-old.

*****

There must have been something my mother felt at the theatre that she wanted me to experience as well. She never said anything specific about it. But after a lifetime of theatregoing, I have a sense of what that feeling might have been.

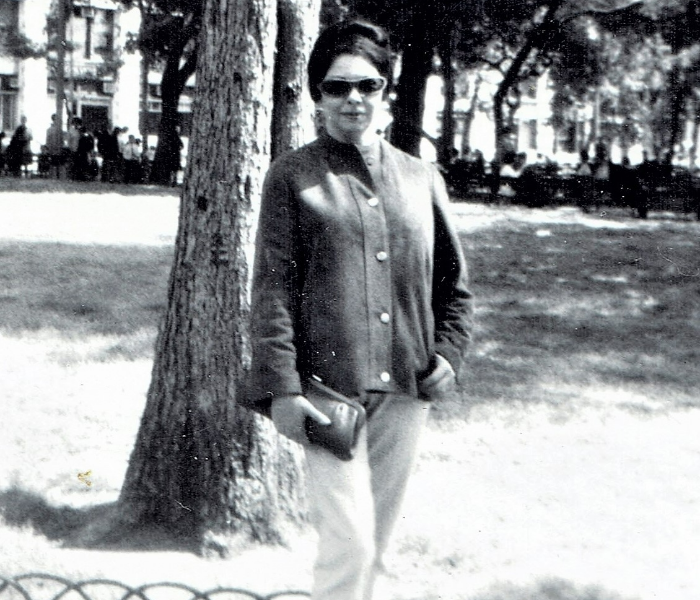

Born in 1919, a child of New York's Lower East Side tenements, her teenage years were colored by the Great Depression. The options for what she could be and who she could become were limited. She became a wife and mother, as so many women of her generation did, and an interior designer, more than many of her peers achieved.

But I grew to detect an aura of unfulfillment, something she never articulated in words but expressed in her moods. Focused on my own experiences during the birthday performances we attended together, I assumed her reactions were linked with my own. But she mentioned occasions when she and my father had attended the theatre and concerts when they were younger; and she would recall nights with her friend and business partner, Eleanor, when they would second act shows, joining the intermission crowd to sneak into the theatre and (usually) find some vacant seats.

Perhaps she glimpsed, and vicariously experienced, alternate life scenarios sitting in the dark; and perhaps, during our birthday excursions, she was projecting some of them onto me, encouraging me to consider options that had not been available to her.

*****

After On the Town, our birthday show tradition closed after an eight-year run. On the brink of adulthood, I made choices based on my own priorities, having nothing to do with my birthday or my mother. I did share a few more performances with her, notably A Chorus Line; a touring production of Gypsy with Angela Lansbury that came to Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts the year my parents moved to Virginia; and a riotous evening with The Flying Karamazov Brothers during one of her occasional visits to New York.

Theatre and concerts were rare for my mother in the last years of her life, while for me they became increasingly frequent; she would experience them through my descriptions. While most performances were not birthday celebrations, sharing some of them with her produced echoes of earlier times.

She died in 1991. For the past 30 years, whenever I can, I rekindle her memory by seeing a show on my birthday, and sharing it with her.

---

Daniel Guss is a native New Yorker. During his career at RCA, he reissued over 1,000 compact discs, ranging from the recordings of such classical superstars as Arturo Toscanini, Jascha Heifetz, Arthur Rubinstein, Enrico Caruso, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Leontyne Price and James Galway, to classical music compilations and Broadway cast albums. He is now general manager of the Early Music Foundation.

TDF Members: Go here to browse our latest discounts for theatre, dance and concerts.