Translate Page

The Tony-winning scenic designer talks about how he made it through his busiest Broadway season ever

---

How can you spot a Beowulf Boritt set? Thanks to "the chameleonic versatility of his designs," as Jason Robert Brown put it in the introduction to Boritt's 2022 book Transforming Space Over Time, you can't—and that's the point.

A prolific scenic designer on Broadway and beyond for the past quarter century, Boritt approaches each project individually, letting the content, his collaborators and the cost determine his vision. Just look at the four disparate shows he did on Broadway during the 2022-2023 season: the 1930s period piece The Piano Lesson featuring a stunning piano adorned with 3D-printed figures; Mike Birbiglia's solo show The Old Man and the Pool and the memory play Ohio State Murders, which both had conceptual sets; and the splashy musical New York, New York, for which he earned his sixth Tony nomination. (He won the coveted prize for his rotating Act One set in 2014.)

Despite his busy schedule—he's currently working on the West End revival of Crazy for You and he recently did the set for Shakespeare in the Park's Hamlet—he still finds time to give back to the theatre community through the nonprofit he founded and co-manages, The 1/52 Project, which provides financial support to rising designers from historically underrepresented groups.

TDF Stages spoke with Boritt about his incredibly eventful season, adding Easter eggs to sets and being visited by Hal Prince's spirit.

Sarah Rebell: You designed the sets for four Broadway shows this year. How do you do it?

Beowulf Boritt: I always wanted to do Broadway shows—I don't think I ever imagined I'd do four in one season! I think the thing that is not taught at all in school is how to manage your life as an artist. Broadway is fast. There's a lot of money at stake. People who can thrive in that situation are people who can manage their time well. What really drove that home to me was when we were teching New York, New York. It's a massive show. We had a lot of time to tech it, but it still wasn't enough.

Rebell: Do you have a standard design approach when you sign on to a show?

Boritt: When I'm developing an idea for a show, I figure out what the set is trying to communicate artistically and narratively. That anchors me because the options are endless. You have to pick something and go forward with it. The Piano Lesson, Ohio State Murders, Mike Birbiglia's latest show, those were all smaller shows. The questions that came were fewer and more controlled, but having a conceptual approach still helped organize things.

Rebell: In both Mike Birbiglia's The Old Man and the Pool and New York New York, you used light and projections to conjure water, but in very different ways.

Boritt: In a one-person show like Mike's, the set has got to take a back seat. The wave became a frame around him to make him the important thing on stage. In New York, New York, I would have loved to have real rain on stage, but you don't want to get the whole floor wet and then ask people to dance on it. The rain scene in New York, New York is as simple as projecting rain onto a black scrim. The scene is very carefully lit, by Ken Billington, so there's light hitting the dancers but not the scrim.

Rebell: There was a lot of buzz around the piano that you and your associate designed for The Piano Lesson. I also noticed quite a few pianos in New York, New York.

Boritt: I have gotten very good at fake pianos this year! We built three different upright pianos for New York, New York because each one has to do different things. My same associate Romello Huins, who did The Piano Lesson piano with me, was in charge of the New York New York pianos. The Piano Lesson piano was quite a bit larger than a normal piano, intentionally, because it was supposed to be this grand, imposing piece. If I'm going to make a piano that's not the size of a real piano, I need to do it very carefully. Once you start messing with the real proportions of things and you're putting this changed object up against a person, it starts to show up when the proportions are off.

Rebell: What about a surreal set, like the askew and suspended bookshelves in Ohio State Murders? Can you play with proportions more easily there?

Boritt: There're certainly more options of what to do. Even in that world of the exploded law library, I was stepping out from the proportions of a real object to a real bookshelf. Then, how I manipulated those in space was more free form. Although there were multiple actors in that show, the set was all about making Audra McDonald the most important thing in the room, which she does very well on her own. But I wanted to do everything I could to support that.

Rebell: You've said said the city is the main character in New York, New York. It sounds like you did the same thing for this big musical that you did for Mike Birbiglia and Audra McDonald: You set up the main character of the city as the most important thing in the room.

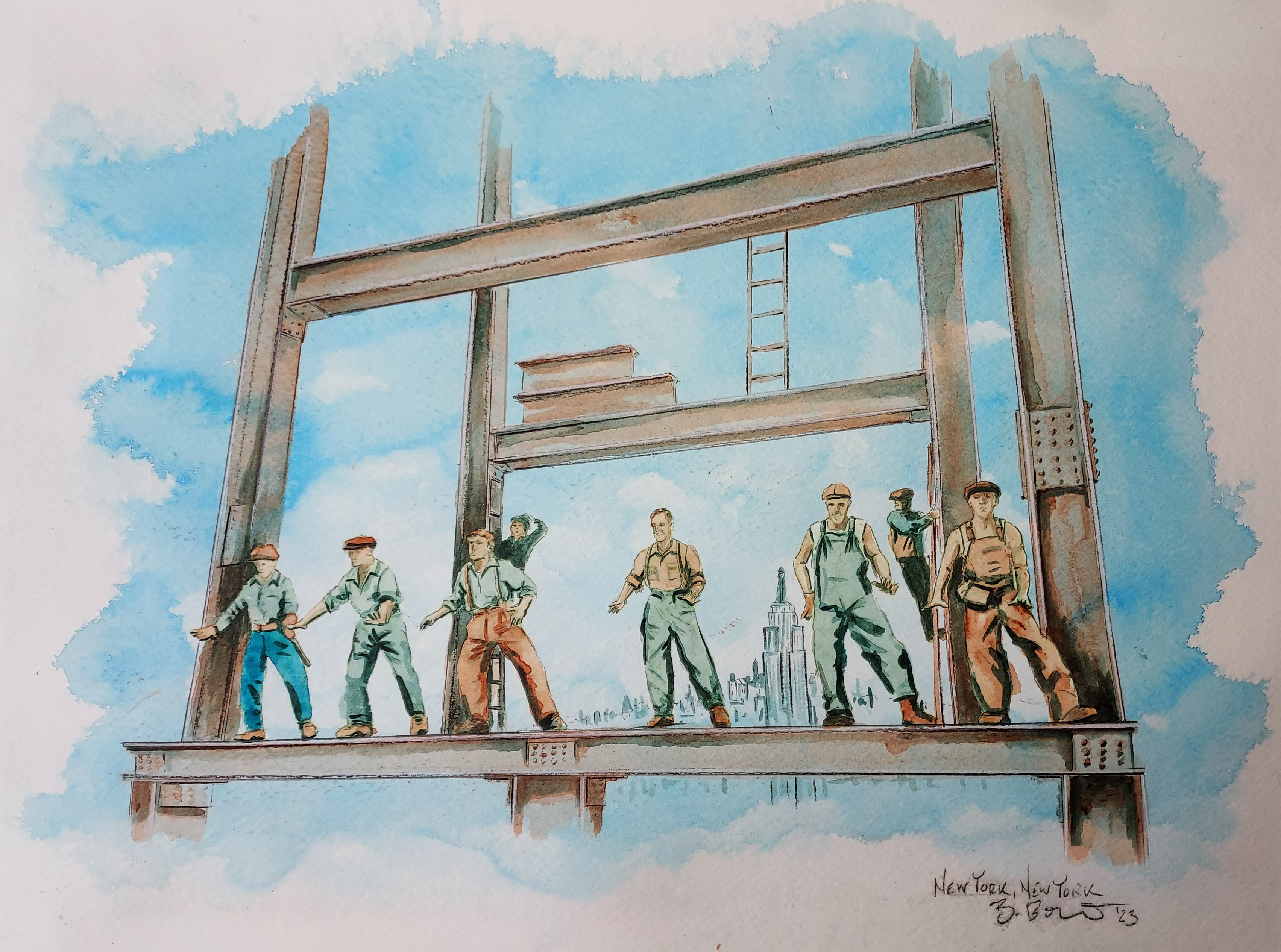

Boritt: That's absolutely true. All of it springs from this basic idea that New York is a living character in the show and, stylistically, wanting to present both the beauty and the grit. I talk a lot about transforming space over time on stage. We make Central Park's Bow Bridge with a bunch of doormen shoveling snow [see the photo up top] and we do a similar thing in Grand Central Station when we go into the Whispering Arch. Because [director] Susan Stroman and I have worked together so much, I knew that if I could give her the right props to create those places, she could make them magically appear and disappear. There were three ideas I pitched to her when we first sat down to talk about the show. Those were two of them and they're still in the show.

Rebell: What was the third idea?

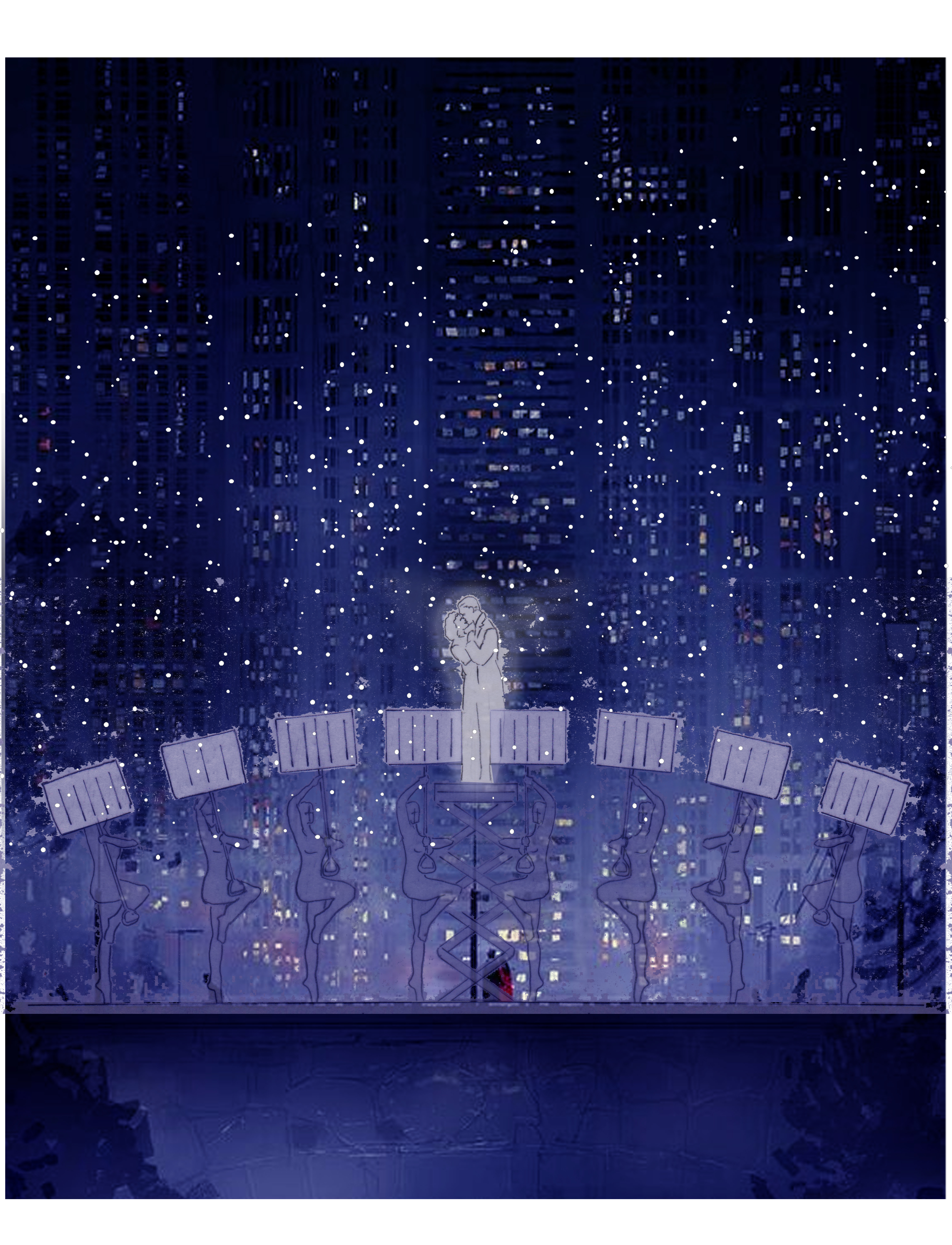

Boritt: The city was going to be a bunch of windows that floated in and out. They would have little seats behind them so you could see people sitting in them. We pursued that for a while, but it became problematic to get actors on and off those seats. In retrospect, although it was traumatic at the time, it was actually good that we had to rethink it. In that moment, I was sitting on the floor of my studio, and I weirdly felt like Hal [Prince]'s spirit walked up to me, tapped me on the shoulder and said, "You know how to do this. Leave a lot of blank space and leave a lot of room for the imagination." It's something that he had said famously many times, but it really felt like he just came over and said that to me. This design clicked into focus in that moment, and I plowed straight ahead. Now there are endless light box windows on the stage and fire escapes because windows and fire escapes imply people.

Also, I want to point out that the show has a bunch of hand-painted backdrops. I feel very strongly about this because it is hard to see a performer against a video wall. This show has 12 backdrops, which is a lot for any musical. Part of what makes them magic is that they're all semi-translucent. They give you this incredible depth. The drops are the gorgeous part of New York, the beautiful sunsets, the glittering skyscrapers or the ceiling of Grand Central. Those moments in New York where the city takes your breath away.

Rebell: On your Instagram, you've been posting Easter eggs from the set. It was fun to watch the show and keep an eye out for the moment when the birthdates of lyricist Fred Ebb and composer John Kander appear on a beam, for instance.

Boritt: Every time you need a detail, it's fun to make the detail have some meaning. The example you just gave of Fred Ebb's birthday is in "Wine and Peaches," the tap-dance number on the skyscraper that's being built. Only Susan Stroman would come up with the idea of making people with a plate of steel on their feet tap-dance on a plate of steel four feet in the air on this narrow little band. The entire, larger set is built around allowing those beams to come on and off stage. But back to the Easter eggs: There are endless pictures of New York construction workers in the '30s and '40s up on high beams. One of the things I noticed in my research is that a lot of the beams had writing that seemed to be some kind of code. It was information for the iron workers who were putting up the beams. I said, "I want to put this into the set." I think it was [book co-writer David Thompson]'s idea that we should make it John Kander's and Fred Ebb's birthdays. Once we put those in there, Kander came into rehearsal and said, "I love it. But Freddy hated for anyone to know when his birthday was." We crossed it out and changed the date by a decade. So, there's a double joke going on in Fred Ebb's birthday.

Rebell: You're the child of a historian. Did your father's methodology influence how you do research for period shows?

Boritt: It probably did subconsciously. When I approach historical stuff on stage, it's not important to me to be historically accurate if the storytelling is made better by being inaccurate. But it is important that I know what the accurate thing is. Because as soon as you start not being accurate, the danger is that audience members who recognize that will be taken out of the story. One of the fantastic research tools that I stumbled onto is 1940s.nyc. When Stro wanted to add a New York trash can, I spent two hours "walking" through the New York of 1941 on that website.

Rebell: While watching New York, New York, I realized there's a connection between 1946 New York and New York now, with the city trying to come back to life after a traumatic event. Has the pandemic had lasting ramifications on set design?

Boritt: The parallels between 1946 and now were quite intentional. But yeah, the pandemic has massively affected design. Part of the reason I'm doing so many Broadway shows this year is because the theatre ecosystem is so messed up. Shows are churning through at a faster rate than they were a couple years ago. And the supply chain issues that everybody's heard about are very true, although it's getting better. We started building the set for New York, New York last September, just to get ahead of all that. But the more lasting thing from the pandemic is that anybody who worked in the theatre, who didn't have enough savings to survive for 18 months, had to go do something else. A lot of people in scene shops just didn't come back afterward. There was a huge knowledge drain and labor drain.

Rebell: You've talked about how Hal Prince was a mentor to you and, in your book Transforming Space Over Time, you wrote about how numerous directors impacted your career. But I haven't come across many conversations about set designers actively mentoring each other. Were there any set designers who opened doors for you?

Boritt: I had a lot of great teachers at NYU, but maybe most notably Eduardo Sicangco, who taught me how to look at musical theatre. When I was young, all I wanted to do was Shakespeare and serious things. He looked at me and said, "Just because it's pretty doesn't mean it can't have an idea behind it." It was one of those moments that really reset my thinking in a massively important way. And it's how I've approached musicals ever since.

But because we're a freelance business, we are, in a very real way, each other's competition. That makes it even harder to form those bonds. One of the things I've done to try to help counteract that was The 1/52 Project.

Rebell: What motivated you to launch that initiative?

Boritt: It sprang from #MeToo and We See You W.A.T., movements that pointed out that design is a white, male-dominated business. There's an immortality to it, and it weakens the industry, frankly. If you have only one point of view, it makes the stories less interesting. 1/52 asks designers with shows running on Broadway to contribute one week's royalties to a fund. From that fund, we pay out grants to young designers from historically excluded groups. We raised $100,000 last year, and we gave grants to seven young designers. I do the fundraising part of it. My hope is that giving people $15,000 allows them to fight on a little bit longer and hopefully get their break. But it's tricky. There is not any official apprenticeship, journeyman way of teaching people.

Rebell: You address parts of your book directly to young designers. You clearly value the passing on of information from generation to generation. Was that part of what motivated you to write the book in the first place?

Boritt: Absolutely. I'm at a point in my career when I get two, three emails a week from young designers asking for advice. I have been asked over and over again, "What's your process? How do you find the design?" The answer is that I figure it out anew each time. It's not very efficient, but art isn't efficient.

Rebell: You've now had a whole theatre season since you first published your book, which I understand is getting a second release. Is there any new wisdom you've learned this year that you want to share with young designers?

Boritt: Probably 1,000 things. The thing I've been thinking about a lot recently is what I said at the beginning: the management part of a career in the commercial theatre. I think it's important not to get lost in your artistic fervor. You can't waste time and you can't waste money if you want people to give you time and money to create.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

---

TDF MEMBERS: At press time, discount tickets were available for New York, New York. The show is also frequently available at our TKTS Discount Booths. Log in to your account to browse all our theatre and dance offers.

Top image: New York, New York stars Colton Ryan and Anna Uzele on a recreation of Central Park's Bow Bridge. Photo by Emilio Madrid.