Translate Page

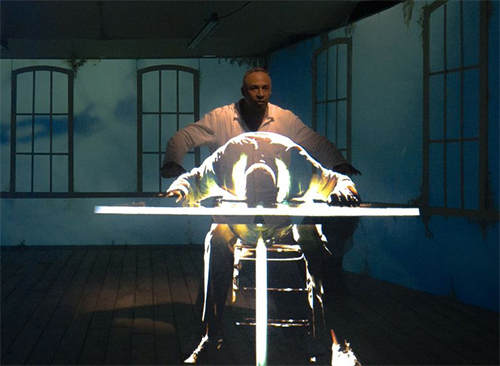

Now at 3-Legged Dog's 3LD Art & Technology Center, the trippy hour-long show features shadows walking independently, bodies flailing in midair, and other impossible-to-believe visuals. All of these haunting special effects come courtesy of the Musion Eyeliner, a high-definition video hologram projection system that conjures 3D images live on stage. But even though the technology seems cutting-edge, its roots date back to the 19th century.

"It's based on an old trick called Pepper's Ghost that was used at Victorian carnivals and in Coney Island funhouses," explains Scruggs, who also has a background in film and serves as 3-Legged Dog's program director. "If you take a pane of glass, place it at a 45-degree angle and light it correctly, it can catch a ghostly reflection that seems to float. Instead of glass, the Eyeliner is a specially designed Mylar surface, but it delivers the same magical effect."

A veteran of the downtown multimedia theatre scene, Scruggs initially used his experiences as a September 11 survivor as the jumping-off point for early drafts of Deepest Man, which focuses on a delusional doctor (Spencer Barros) whose wife drowned in an unnamed, Katrina-like disaster.

"I was the director of technical services for Windows on the World and happened to be on vacation on 9/11," Scruggs explains. "And for the past few years I've been working here at 3-Legged Dog just a few blocks from where the Twin Towers stood. At first I was interested in exploring the idea of disaster capitalists, who profit off of tragedies, versus survivors, who just want to get back what they lost. But it turned into a piece about water and diving deep inside yourself and how people deal with extreme emotions like grief."

He refers to Deepest Man as a "collage," which is fitting. It's a mixture of disparate elements with a nonlinear and surreal narrative that touches on a wide variety of topics. "I was wrestling with several things while developing this piece," Scruggs says. "There's stuff about organized religion, the power of Oprah and other celebrities, how people will go on TV and reveal their darkest secrets, and of course, free-diving as a form of healing."

Free-diving, the extreme sport of going as deep as possible underwater without the benefit of a breathing apparatus, is a recurring motif. The protagonist even submerges his face in a bowl of water for minutes at a time as his thoughts appear onstage thanks to the Eyeliner. "If you're stressed you can't do it," says Scruggs. "You have to calm yourself down and face your demons. Spencer holds his breath for almost two minutes! Your blood pressure and heart rate drop automatically. It's amazing---your body just does these things. It sounds really corny, but I think free-diving makes you a better person. I've met several free-divers and they're all so Zen."

Since Scruggs wanted to try to communicate the unique sensation of free-diving, he knew from the outset that he would need to utilize 3-Legged Dog's treasure trove of high-tech gadgets and in-house wizards. "I was already working here at the theatre when I was writing this, and I was very aware of the technology we had to work with," he says. "We have this R&D room we call the 'Nerd Nest.' The guys in there are extremely skilled. and I kind of wrote the piece with the Eyeliner in mind. A lot of the images in Deepest Man couldn't be done easily without it. When I first brought the show to (executive artistic director) Kevin Cunningham, he said, 'James, I invite you to think bigger.' I almost broke into tears. You so rarely hear that as an artist."

But for all of the Eyeliner's power, it's an actual, not virtual, set piece may deliver the most striking visual in the entire show: the climactic disaster sculpture, a jumbled mass of detritus which serves as a metaphor for the doctor's fractured psyche.

"We were inspired by images from tragedies where Mother Nature rearranges things," says Scruggs. "Of course it's horrific that people got hurt or killed, but when looking at these photos, the juxtaposition of twisted metal and trees is strangely beautiful." Although it took weeks to construct, the audience only glimpses it for a few seconds before the lights go out. But it's a potent image that's hard to shake. "I wanted to pull back the curtain and show everyone what was just beneath the surface," Scruggs says. "This is what survivors carry around inside."

---

Raven Snook writes about theatre for Time Out New York and has contributed arts and entertainment articles to The Village Voice, the New York Post, TV Guide, and others.

Photo by Juliano Chiquetto