Translate Page

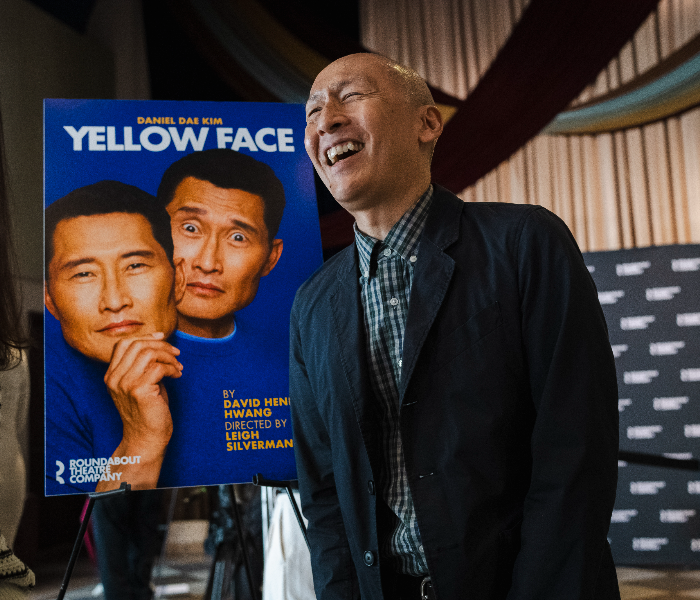

Francis Jue, who is reprising his acclaimed performance in Yellow Face on Broadway. Photo by Marcus Middleton.

Why director Leigh Silverman and actor Francis Jue were so excited to return to David Henry Hwang's satire two decades on

---

Part of the fun of David Henry Hwang's Yellow Face, currently running at Broadway's Todd Haimes Theatre, is sorting out fact from fiction. A witty and subversive satire about racial identity and prejudice, the show is a mockumentary with a fictionalized version of the playwright, DHH (played by Lost star Daniel Dae Kim), at its center. Hwang incorporates events from his own life, notably the protests he helped spearhead against the yellowface casting of white actor Jonathan Pryce as a Eurasian pimp in the 1990 Broadway production of Miss Saigon, and his notorious 1993 Broadway flop Face Value, a farce about mistaken racial identity that closed during previews. Simultaneously, he explores the disillusionment of his immigrant father, Henry Y. Hwang (HYH in the play), a banker who loses his faith in the American Dream after being accused of laundering money for China in The New York Times.

While Yellow Face received mixed notices for its world premiere at The Public Theater in 2007, it won an Obie Award and was shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize. Seventeen years on, Hwang has made some tweaks for this Roundabout Theatre Company mounting—it's now one act instead of two—and considering the rave reviews, it's a comedy whose time has clearly come.

Two things that have remained the same for both productions: the director, Leigh Silverman, and actor Francis Jue, who's reprising his award-winning performance as HYH. TDF Stages spoke with Silverman and Jue about their love of collaborating, the play's prescience and why the theatre industry still has a long way to go when it comes to Asian-American representation.

Gerard Raymond: What's it like returning to Yellow Face in 2024, when identity politics are more pervasive and divisive than ever?

Leigh Silverman: I think the play is even more relevant. This whole production really came about because, in one of the low moments during the pandemic, I called David and said, "It's a shame that we'll never go back to the theatre and there will be this whole generation of people who won't know Yellow Face. We should record it for Audible." He thought that was a great idea. Of course, by the time we did record it, theatre was back! But as we sat around the table reading the script, it was so clear that the time had come for a Broadway production of this show. The way that our culture has moved, the play went from being something that was more niche to being something that was actually part of everybody's cultural conversation. It made the things that are being explored in the play funnier because more people knew about them.

Francis Jue: Even 17 years ago, I thought this play deserved a wider audience, because it wasn't just about theatre high jinks and backstage bitchery. It was also about who gets to decide who is American and who is Asian, and it dealt with politics, family and the media. I met Leigh through this show. Since then, I've worked with her so many times, both with and without David. It's just been the most amazing relationship.

Silverman: I was put together with David in 2006 by Oscar Eustis, a longtime dramaturg for David who had just taken over The Public Theater. We had moved Well [a play about Lisa Kron's relationship with her mother] to Broadway from The Public, and Oscar said he had this autobiographical meta-theatrical play about David and his father. I was very eager to meet David, but we had a not great first date as director and playwright and I was bummed. Then the next day he called and said, "You know, I don't think you understand the play. But you were so honest and clear that it made me feel like I actually need your kind of feedback to write the play that I want to write." That was the beginning for us [the two went on to work on Soft Power, Kung Fu, Golden Child and Chinglish]. And the more I can rope Francis in to get into some trouble with us, the better. I'm just so privileged to have collaborators like Francis and David, and to be able to bring this amazing play to Broadway right now.

Jue: I get really jealous and mad whenever Leigh works on a project without me. I mean, I could have been in Suffs. What the hell?

Raymond: Leigh, David claimed you misunderstood Yellow Face the first time you read it. What did you learn about the play as you two worked on it?

Silverman: David has written a kind of mockumentary. In the course of the show's development, it also became this political play and, ultimately, this very personal play about his father. I talk about Yellow Face as a shapeshifter because it starts out as one kind of show, and then it opens out and opens out. David is addressing bigger questions about what it is to be Asian American in this country.

It's fun to direct because you have to be really grounded in what style and tone the show is taking on at different moments. David trusts the audience to be able to move through with us. Because of that, the production on Broadway has a complex, almost farcical kind of presentation. We have double turntables, LED screens and video projections. But when the play finishes, we have simplified it way down to an almost completely bare stage. Part of the journey of watching the show is discovering the transformation of style over the course of the night. It allows David to do a lot of different things—to braid truth and fiction in ways that are unexpected and tantalizing. That treasure hunt he sends the audience on has been very fun to serve up.

Raymond: As artists working on the show, did you need to know which parts of the play are fact and which are fiction?

Silverman: I do know at this point what's true and what's not, but for my purposes, it's all true. We have a lot of real people inside the show, and our goal is not verisimilitude, but to capture an element or a feeling about that person. I feel that everybody we represent onstage lives inside of this world, which feels enormously like ours and also just a little delightfully twisted. We have women playing men, men playing women, people of different races playing each other. We are simultaneously exploring casting and representation in the content and form of our show.

Raymond: Francis, what's it like to portray a version of the playwright's father on stage?

Jue: The first scene I ever read from this play was the first phone call between David and his father. It really is, I think, the point of the play. The Broadway high jinks, everything about the media and how Asians are portrayed, donor gate and the investigations of Asians in the '90s, all boil down to whether or not David can integrate his father's American Dream into his own life and career. David didn't say much to me specifically about his dad, because it wasn't about imitating him. In fact, I saw a photo of Henry Y. Hwang for the first time only about a week before we started rehearsals this time around. But one of the things David said to me that really sticks out is that his dad stood tall. When his dad entered the room, he was the star of that room—he took up all the oxygen. And that is reflected in the script. I think that everyone wants to be the star of their own life. Asian Americans and, I think, other marginalized groups are acutely aware that even if they're trying to be the star of their own life, they're being defined from the outside by other people. We are only allowed to be certain things. David's father believes he's the star of his own life, and in many ways succeeds at that, until he can't. The best compliment I could ever have received was when David's mom came to see the show at The Public and, afterward, she took my hand and said, "You don't look like Henry, you don't sound like Henry, but for the last couple of hours, I felt like I was spending time with my husband again."

Raymond: Why do you think comedy serves the serious ideas within the play so well?

Silverman: David is using himself as a foil. He's really the butt of all the jokes in the play. Throughout the show, the character of DHH is posturing as this Asian-American role model, but he has lost his true identity. At the beginning of the play, he is the leader of the Miss Saigon protests and then the dilemma is when he accidentally perpetrates yellowface in one of his own productions. In the best tradition of farce, our lead character, DHH, knows the least out of everyone. He is an unreliable narrator. I feel like the comedy of the play works best when it's approached with seriousness because it comes out of high stakes. I think David is drawing the connection—first in a very funny, entertaining, farcical way, but then, ultimately, in a very serious way—from yellowface to the racism that Asian Americans face in this country. Your heart is just open because you have been laughing—it's so brilliant.

Raymond: How did the play evolve for the Broadway production?

Silverman: It had originally been written as a one-act but then everything was too long, and David didn't know exactly where to cut. So, we made it two acts at The Public and also for Audible. In this production, we have finally gotten back to the one-act structure that I think helps the overall tone of the show and keeps the pace going. We also reoriented some of the parts: Francis got pulled out of most of the ensemble work and his track is specifically HYH. At The Public, David felt in terms of casting that it was a binary world: We had Asian Americans and we had white people. For Audible and also this production, he wanted to change that. So, we have this incredible duo in Marinda Anderson and Kevin Del Aguila who play 26 or 27 roles each and who are not part of that binary world. I think David was able to find a way to both articulate who their characters are and what their lived experience is on stage, and also expand our understanding of how race can work inside of our show.

Raymond: Francis, do you think the entertainment industry has improved for Asian-American actors since Miss Saigon?

Jue: I'd say that there has been change but there hasn't been enough. Since Miss Saigon, there's been a change in attitude not just about the casting of roles, but also about the show itself. I think that we have made some progress in many ways, but there are still recent examples in television and film where Asian characters are either played by non-Asians or the characters themselves are transformed so a non-Asian person can play them. We still haven't had our A Raisin in the Sun, where you just have a family onstage, and it becomes part of the American cultural conversation. There was a survey recently about whether people could name an Asian-American or Asian star at all. And the majority couldn't name a single person! I think we still have a long way to go. One of the remarkable things about Daniel Dae Kim in our production, from the moment he steps onstage, people identify with him. That's something that blows my mind. He's a bona fide star and not just in terms of clout or Hollywood, but culturally he's somebody who, whether you're Asian or not, people identify with. I think that is actually very, very new and I'm here to celebrate that with this show.

Raymond: Is the play being received differently on Broadway than it was downtown 17 years ago?

Jue: Back in 2007, Obama was running, and we were post-racial, right? Even people in our industry were saying, "Why is David still writing about identity? We've got a whole new generation of Asian-American writers and actors, so why can't we just be people?" Now we're faced with really basic questions about identity and about who we say we are. What is theatre doing in the middle of all of this? How do we advance those conversations? Isn't that what we're here for? Because all of those things are so front of mind, I think our show is that much funnier and people are that much more engaged and sympathetic.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

---

TDF MEMBERS: At press time, discount tickets were available for Yellow Face. Go here to browse our latest discounts for dance, theatre and concerts.

Yellow Face is also frequently available at our TKTS Discount Booths.